We've now got smartphone operating systems like Android and Windows Phone that are centred around 'the cloud', i.e. online data storage - whether it's PIM data, music or photos or (heaven forbid) video. The thinking, for the tech-savvy urbanistas, is that there's little point in having much content actually on your phone because it's cheaper and simpler to keep it all online - where it's backed up for you and available on every device you own. Sounds good, except that there's the assumption of more or less constant connectivity available in unlimited quantity at a presumed flat rate of expenditure.

Travelling from small town to small town in Devon, Somerset and Avon in the UK, I've been keeping track of the mobile connectivity available. We're not talking a few sheds out in the countryside here, we're talking towns of a few thousand people at minimum - and I've only seen a 3G symbol on my smartphone once ... for about ten minutes. The rest of the time it's been EDGE data if I'm lucky and GPRS as the most common means of getting online. In some villages, there was zero cellular signal (on both of the networks I had SIMs for) and thus not even GPRS. Nothing.

Yet the data speeds being talked about (and assumed) by the cellphone industry, from adverts to spec sheets to product launches, are in the order of ten times faster, sometimes even as much as a hundred times faster (LTE versus GPRS, for example!) That's quite a disconnect from reality.

90% of the time, I had GPRS connected and picking up email on my phone wasn't a problem. Using Gravity on my Nokia 808 or 'Rowi' on my Lumia 800 to pick up tweets and even summarised Google Reader feeds was possible, if a little slow. Mobile web sites, provided I was careful, were usable. But full desktop sites, images in general and the use of application stores were all a no-go area much of the time. A smartphone without much connectivity is still smart in that it's a converged device with apps and communications functions, but it's rather crippled.

Interestingly, since this article being co-hosted on All About Symbian, it's worth noting that Symbian fares better than most other mobile OS here, in that it's designed to work with low bandwidth from the start. Most applications (e.g. music, photos, video, maps, etc) assume content has been sideloaded onto mass memory or a memory card. There's little concept of music being continually streamed in from the cloud. Even more so video (in fact, Symbian's particularly bad at streaming online video in my experience).

Of course, this shouldn't be altogether surprising, seeing as Symbian came out of a world where data was a trickle if you were lucky. Back in 2006, 3G was a novelty and very few applications expected a working Internet connection. The Nokia N95 was typical for its time and represented a good balance between phone and multimedia computer. In deriding the latest Nokia 808, critics have mentioned that it's effectively a 'glorified N95' - the intention is as an insult, but it's a pretty fair observation. The 808 can exist, from music to video to maps to games, with little need for high speed connectivity, provided a little time is allowed for sideloading and setup before one embarks on a data-starved trip.

Let's return to the data disconnect. I looked around at people going about their daily business in these UK towns - no one seemed too concerned that their lives weren't revolving around high speed Internet on their phones! We often talk about us geeks living in a 'tech bubble', concerned over issues that simply never occur to the general populace - connectivity is just another example of this. It also highlights the yawning chasm between the expectations of the Silicon Valley elite and the lives of regular people, whether in semi-rural UK or semi-rural anywhere else.

My initial rant, linked above, was from four years ago - tested here in 2012, coverage still hasn't improved. City-based reviewers often talk of a device being slow to download heavy duty web pages - indeed this accusation has been levelled at Symbian in particular many times, implying that the bottleneck is the device's processor, OS and web rendering code. While this may be true if the phone is being tested 250 meters from a 3.5G or LTE cell tower, it's patently not the case for the vast majority of real people out in the real world, for whom the bottleneck for all online activity is the data stream itself, down to 5kbps quite routinely for me this week.

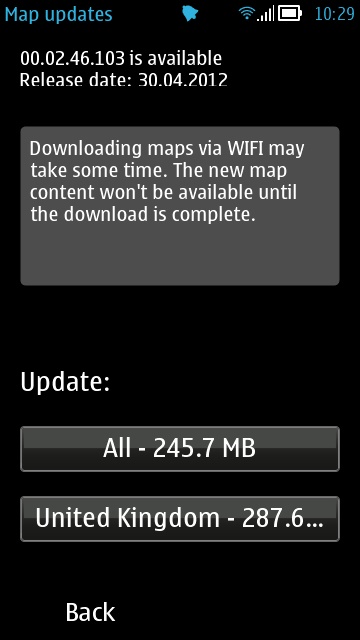

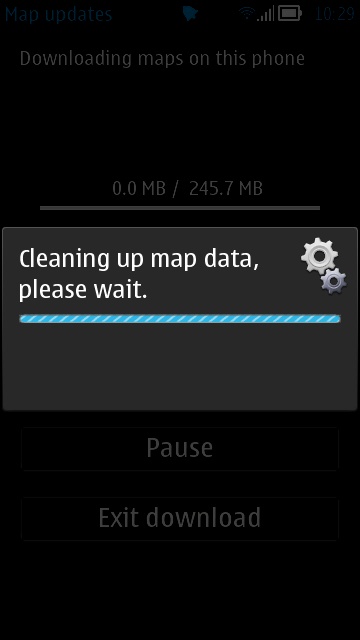

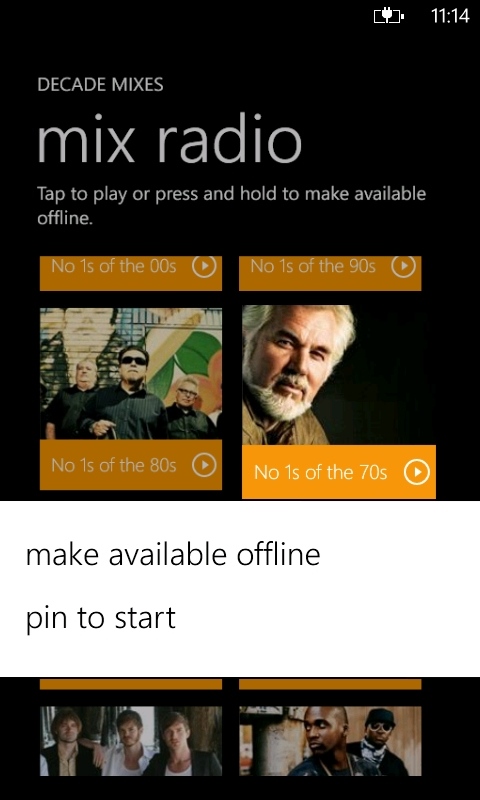

It was somewhat telling that both my Lumia 800 and my Galaxy Nexus, both with '2012' operating systems and both with limited internal storage (16GB) were somewhat crippled in terms of how I'd normally use their interfaces and functions in the absence of even moderate speed data. The Galaxy Nexus was almost reduced to being a sleek black brick, with Google Maps 'offline' functions being utterly laughable - at least the Windows Phone was able to provide Symbian-style offline navigation thanks to the ability for me to have preloaded all the UK's maps before I left. But it was left to my Nokia 808, running the relatively ancient Symbian OS, with its data and battery efficiencies, with its internal 16GB mass memory, plus (in my case) 32GB microSD, to provide me with (sideloaded) movies, music, maps and more on my travels.

Will the situation improve across, in my case, the UK? I'm doubtful. There seems to have been almost no progress in terms of 3G rollout for the West Country in four years, which is somewhat criminal. Is setting up 3G towers really that expensive? Surely the various networks could club together and work out some kind of cost-sharing or tower-sharing arrangement? Surely sticking in repeaters on major routes and for anywhere with a population of more than a few hundred shouldn't be prohibitive in the grand scale of things?

Because, as I see it, the data disconnect is getting larger and larger. What on earth is the point in more and more graphically lavish applications that pull in a Gigabyte or two per month of cellular data, when using them is, for a great many people, just about impossible because the data speeds are too low? The smartphone experience in (say) San Francisco or London is very, very different to that in (say) Minehead, Somerset, where I spent the day yesterday, a seaside town of around 15,000 people that survives on two 'bars' of GPRS.

Much is made of 'fragmentation' in the smartphone world, but I reckon that the data disconnect should be bundled in with OS and form factor issues, since its effects are even more dramatic in heightening the gap between the smartphone 'rich' and the smartphone 'poor'.