What's more unusual about the deal is the emotional impact of the announcement and transaction. This partly reflects the close association consumers have with their mobile phones; the fact that Nokia is the grand old lady of the mobile phone manufacturer world; and the affection and admiration with which Nokia is regarded, especially in its home market of Finland. The emotional factors are not altogether irrelevant, most especially for current Nokia employees and Finns in general, but it is quite clear that to understand the basis for the deal, emotion should be taken out of the equation.

Microsoft has published a presentation that detailed its strategic rationale in negotiating the transaction. The absorption of Nokia's Devices and Services business ties into the Redmond-based company's strategy to become a devices and services company (the "One Microsoft" vision). Once Microsoft's devices and services strategy became clear, the acquisition of a major device manufacturer became more likely, with Nokia, given its close existing relationship with Microsoft, the most likely candidate.

The transaction gives Microsoft a significant stake in the mobile phone device business, with shipments of more than 200 million devices a year. A significant volume of devices is something that's going to be absolutely essential if Microsoft is to truly become a "devices and services" company. Mobile phones are at the heart of this strategy simply because they are the most common and personal consumer electronics device. Microsoft continues to believe it is important to control its own platform on devices of all kinds because it reduces the risk that it will be locked out (i.e. it doesn't want to be dependent on Apple or Google) and improves the economics of the business (i.e. not sharing a portion of revenues).

On the financial side, a good case can be made that the deal makes sense. The €5.4 billion that Microsoft is spending looks to be relatively good value, especially when the terms of patent licensing are examined in more detail (10 years, plus option for perpetual license). The pace and scale of change in the mobile industry can easily be seen by comparing the value of today's transaction with that of Microsoft's purchase of Skype ($8.5 billion) and Nokia's acquisition of Navteq ($8.1 billion).

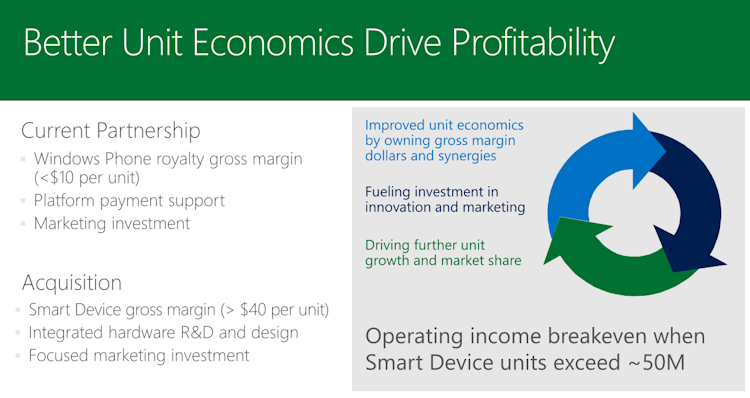

Microsoft believes it can increase the gross royalty margin on every Windows Phone device from the current value of less than $10 to more than $40, but it's hard not to see that as anything other than optimistic, in the face of fierce competition from Apple and Google. However, Microsoft also indicates that there will be operating income break even at a volume of 50 million devices a year, close to the 12.5-14 million devices per quarter we recently estimated as the break even point for Nokia's smartphone business, something that appears to be eminently achievable, even in the relatively short term.

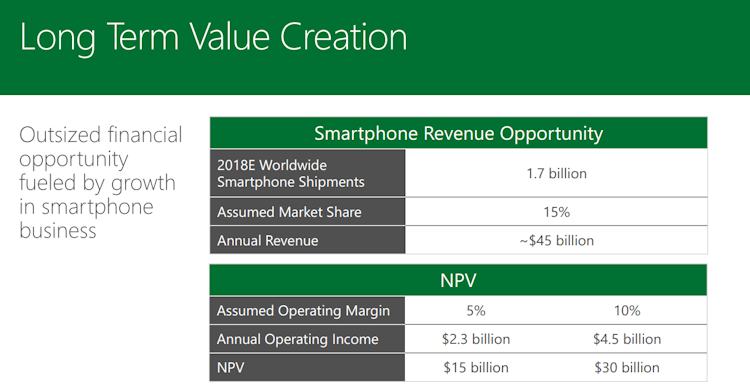

In the longer term, Microsoft says it is targeting a smartphone volume market share of 15% by the end of 2018 (255 million devices per year). With an assumed operating margin of 10%, that would see an annual operating income of $4.5 billion. All of these financial numbers do assume that Microsoft can effectively execute on its devices and services strategy, absorb Nokia's Devices & Services business, and maintain or improve the current level of design and product (device) innovation.

Critical to Microsoft's success in absorbing Nokia's devices business will be finding a way to manage, and in the longer term merge, the two very different corporate cultures of the constituent components of this deal. Maintaining the Nokia culture is, arguably, going to be key to creating a successful devices and services business in the mobile phone space. While 'culture' is a somewhat woolly concept, it is possible to argue that it is what has set Nokia apart from other mobile manufacturers, and has been a key ingredient in the company's strong design and hardware track record.

So, the transaction makes strategic and financial sense from the Microsoft side, albeit with a significant gamble attached to successfully absorbing the Nokia device business and culture, but there's still an element of 'why now?' Microsoft could have purchased Nokia at any time in the last two years, but chose not to do so - because there was no reason to do so. This can be said to have changed with Microsoft's shift to become a devices and services company, but the move, even looked at in this context, still feels a little premature.

The answer is to look at the transaction from the Nokia viewpoint. No one would dispute that such a deal has been a possibility ever since Nokia switched to using Windows Phone, but even so the timing of the announcement has caught many by surprise. With hindsight, the timing now appears to be the result of the slow progress made by Nokia's Windows Phone strategy, an uncertain outlook, and upcoming debt restructuring. An upcoming "recommitment date" in the Microsoft Nokia partnership may also have been a catalyst and leverage for Nokia in determining the timing of the transaction.

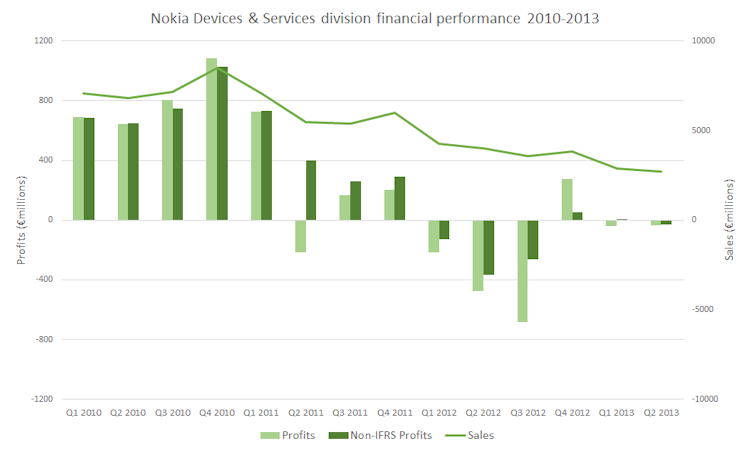

For the Nokia Board of Directors, the transaction is about maximising value for Nokia shareholders. The smartphone section of the business has been losing money, and that looked set to continue for a minimum of another three quarters. In that context, it's not hard to imagine a large number of shareholders breathing a sigh of relief that a transaction agreement has been entered into with Microsoft. That may be in sharp contrast to the feeling of many of Nokia's fans, but it's shareholders to whom the Board of Directors are accountable.

The half of Nokia that Microsoft did not buy comprises a valuable and sustainable business, which will benefit from the injection of capital arising from the transaction. The Advanced Technologies business (CTO office, NRC, and related research and development) is a bit of an unknown at this time, NSN's infrastructure remains as necessary as ever (and the division recently returned to profitability), and HERE's location platform holds a great deal of potential (and looks better off outside of Microsoft, given its horizontal strategy).

The patent section of the deal also looks interesting for Nokia shareholders. A price of €1.65 billion over ten years translates into an annual licensing run rate of €165 million, providing a basis for the price that other companies may have to pay if they want to license Nokia's patents. The patents side of the business will provide Nokia with a healthy income and the potential capital to develop further research and development opportunities. How effective that can be in the absence of a matching devices business remains to be seen, but that's not a major issue in the short term.

So, from a financial point of view, the transaction, in the context of Nokia's current difficulties, is reasonably attractive to the company's shareholders, something that is reflected in a 30% rise in Nokia's share price today. Yes it's a far cry from Nokia's valuation of €110 billion in 2007, and the enormoous destruction in shareholder value during the intervening period is not a happy story, but the potential transaction should be judged in the context of current circumstances and potential future performance. However, as with the Microsoft side of the deal, there's still the question of timing. Why now?

The aforementioned "recommitment date" may have had a significant role. This date, most likely sometime in February 2014, would have represented a break point in the Microsoft and Nokia contract. Up until today it was assumed that the contract was fixed for five years, but that now appears not to have been the case. The terms that make up the break clause are unknown, but the prospect of Nokia backing away even slightly from Windows Phone (e.g. by telling Microsoft it was going to do an experimental Android device) may have been enough of a catalyst for Microsoft to pull the trigger on the transaction. Whether any potential action by Nokia was realistic is not really the point, the risk to the credibility of Microsoft's mobile strategy would have been too great for Microsoft to ignore.

A second factor is Nokia's financial situation, which may have added to the pressure to get the deal done. It's clear that Nokia's smartphone business has been losing money for at least two years, gradually eroding Nokia's cash position. This has been offset by a series of platform payments from Microsoft, but not by enough to halt a decline in the net cash position disclosed in each set of Nokia's quarterly results. A true measure of Nokia's cash position is hard to ascertain due to the number of assumptions that have to be made, but, with the benefit of hindsight, it is not unreasonable to suggest that Nokia would have faced substantial difficulties in the near future, sooner than the disclosed position might have previously suggested (i.e. somewhat hidden by Nokia's careful management of working capital). This, together with the refinancing of debt that was due early next year, may have been the catalyst for getting the deal with Microsoft done sooner rather than later.

Both Nokia's financial position and the upcoming "recommitment date" suggest that Nokia may have been more central to the timing of today's announcement that might otherwise be assumed. The implicit assumption in this is that proceeding as things were, with the Windows Phone strategy remaining in place, was no longer considered a viable business or financial option for Nokia. Better then to sell at the point at which maximum value could be obtained for shareholders. Once that point was reached, Microsoft, given its new devices and service strategy and the importance of Nokia to its Windows Phone business, had little choice but to enter into an agreement to acquire Nokia's Devices & Services business.