Let's start with my favourite number from the survey. The number of users who make a purchase from inside an application is 1.5%. That's in the same ballpark as the number of users who convert from a trial version to a full priced version of a piece of software. For all the 'we don't want freemium we want the old model', when you take it back to looking at the money (which is the driving force for many app developers), freemium not only matches the return from the shareware model, but provides more income through variable pricing and ongoing revenue.

The twist of course is that the idea of what a game is, and what you are downloading, has changed over the last few years. It's hard to debate a game that is 'missing elements' or makes something 'almost impossible' but will unlock these features when you buy the full priced version, because that's the obvious bargain you get when using a trial version.

Freemium takes the same approach - if you want certain things, then you are going to have to pay for them and unlock them. The difference is that mentally you are not downloading a 'trial' version, you have downloaded a full game. Yes it's free, but the expectation is set differently.

I suspect that this is what drives traditionalists up the wall about the freemium model. If we were to call them trial modes, rather that free apps, then there may be a better understanding - but very soon we'll be in a significant minority. The gamers of today would scoff at the idea of a 30 day trial and then send a cheque in the post, just as many old timers now scoff at the idea of free to download and pay to play.

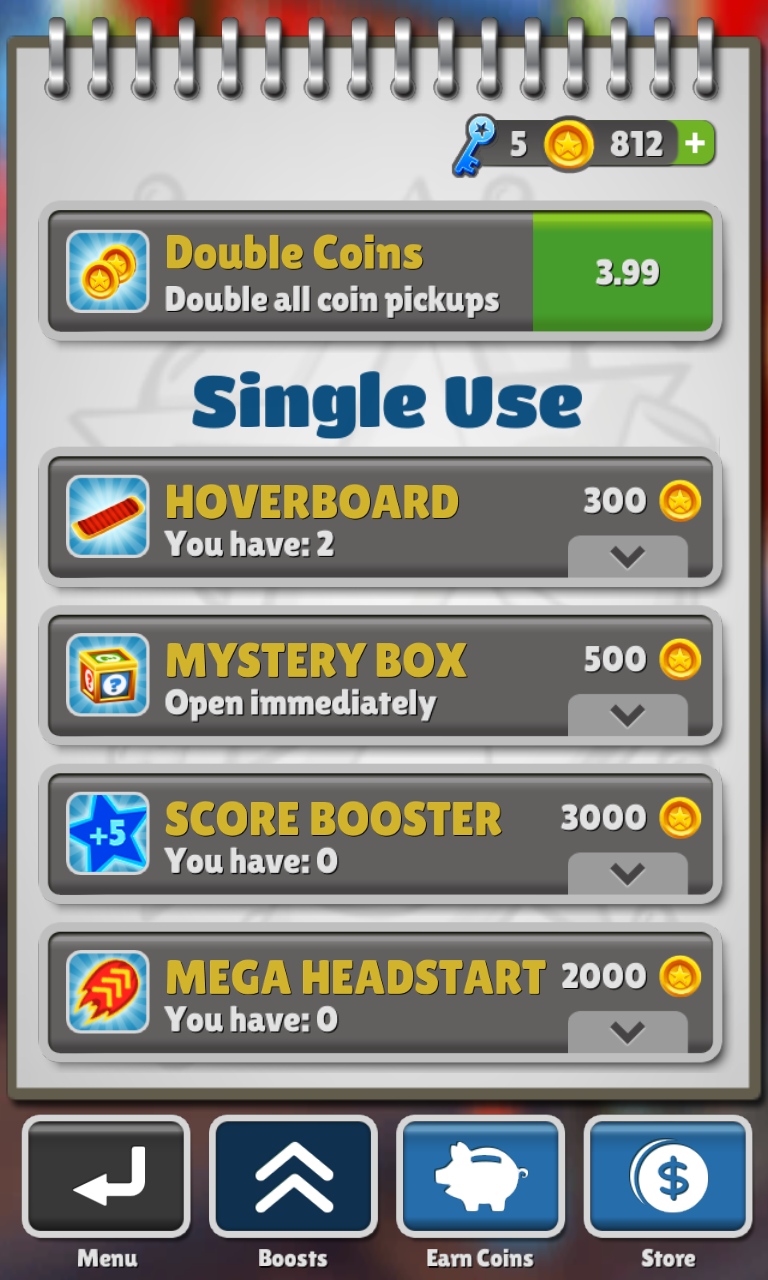

Subway Surfers offers a one time 'unlock' booster, or the opportunity to buy coins with In-App Purchasing

But freemium is more than the renaming of the old shareware concept. Freemium adds another level of income for the developer. Recurring income.

While many freemium games have worked well with single purchases to unlock the rest of the content, this still keeps the income levels at the old shareware levels (and in the case of Android, the vastly increased levels of piracy compared to older platforms from five or ten years ago). The freemium model (especially timer-based games that offer you currency boosts through in-app purchasing) allows users to keep making payments if they wish, and that allows developers to have an ongoing income.

This is where the big money can be made. While the poster child apps of the ongoing freemium income are not available on Windows Phone (I'm thinking of Clash of Clans and Candy Crush Saga here), there are countless games that get the balance just right, where people can play 'for free' and still have a good experience, but also allows players who wish to pay to have a positive impact on their app either through a single payment or an ongoing, almost subscription like, payment to the developers.

Clash of Clans, one game that monetises very well through in-app purchasing.

Sometimes it doesn't work out, the in-game currencies cannot be earned in sufficient volume, forcing you to the in-app purchase much more quickly. Those in-app purchase levels may simply be too onerous to allow for a good gaming experience. But there are countless examples from the shareware and trial/full price days when the balance point was not quite right. Good design counts as much for IAP as well as for graphics or sound.

Like any tool, in-app purchasing needs to be used correctly. The basic levels of competency match that of the older shareware model, but in-app purchasing offers much more reward when used correctly. You should never forget that it's the easiest thing in the world for a user to simply stop paying in a freemium model.

That's why I am glad to see that Microsoft's Windows Phone Store supports those who want to remain in the trial mode for game and app development, with SDK support for the trial modes, but also allows for the robust use of in-app purchasing through the same payment system (which can be PIN code secured on your Windows Phone handset).

Just as our smartphones have evolved, so have the mechanics and the monetisation of the apps and games we play. Developers now have more opportunities to earn a living from mobile gaming, gamers have more opportunities to 'try before they buy', and manufacturers have far more third-party options for their mobile devices than at any point previously.

Swrve tells us the macro economics of game development on mobile has not been stunted by the growth of freemium. Far from it, it has contributed to the growth, success, and expansion of mobile gaming into the powerhouse it is today.