How Xenon flash works

There's nothing proprietary about using Xenon flashes, of course, they've been around in standalone cameras for decades. Whereas LED flashes are just that - very bright LEDs and are very simple, Xenon flashes require rather more in the way of electronics.

Essentially a (large) capacitor's charge and voltage is ramped up such that it can discharge into a narrow tube filled with Xenon gas. The electrons in the gas jump to a higher energy state and then, a micro second after the discharge, jump back to their original energy state, emitting light as they do. Xenon is chosen because the state transition emits light in in several spectral lines, giving the appearance of a 'white' flash - other inert gases would produce light that's too red or not visible to the human eye at all.

Add in a reflector and you've got yourself a Xenon flash, capable of lighting up a room. My usual rule of thumb used to be that a Xenon flash is ten times brighter than LED and a hundred times shorter in duration, though recent advantages in LED flash technology have meant that the factors are probably nearer five and fifty nowadays.

The Xenon bulb on the Nokia 808, probably the most powerful flash ever put into a smartphone...

Advantages and disadvantages

The use of Xenon certainly isn't clear cut, as you can see from my table below:

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| LED flash |

Cheap to implement Minimal supporting electronics Can also function continuously, as a video light, or to support a 'burst' mode |

Relatively dim, so shutter speeds have to be quite slow - any motion in the subect will result in blurring |

| Xenon flash |

Very bright Very short flash duration, so can 'freeze' motion |

Expensive to implement Requires a sizeable capacitor (though see here) Requires a certain 'recharge' time, typically of the order of a second |

A lot really depends on what you want to photograph in low light. If it's just your food or something (close and) properly posed then LED flash may well suffice. Whereas if you're shooting moving people (especially kids) then Xenon is a must...

Examples of LED vs Xenon flash

In practice, it's fairly easy to tell a Xenon-lit shot from an LED-lit photo. Take the same photo in an indoor social situation (e.g. down the pub) and the Xenon-lit shot will be ultra-crisp, faces and bodies are frozen in time, but the background to your main subject is usually quite dark, since the camera (phone) is exposing for the subject in focus. Here's an example from the 2010 Xenon-equipped Nokia N8:

In contrast, the LED-lit scene will be just that - more of a scene, with the background showing up evenly, but with your main subject usually slightly blurred through their natural motion (breathing, smiling, whatever), with this example shot on the 2012 Nokia Lumia 920:

Quite a dramatic difference between the two shots, though which you'd consider the better photo depends entirely on what you wanted from the shot in the first place.

It should be noted that most phones, including those with Xenon flashes, also have a 'night portrait' scene mode, in which the flash is fired but the shutter's left open for longer than strictly needed, in order to gain some of the context, the background, and thus (in theory) get the best of both worlds. This can work well for posed shots, but you run the risk of still getting some blurring around the Xenon-frozen parts of the image. As a result, 'night portrait' is very much a scene option rather than the default.

Here's another typical Xenon-lit example, showing the people crystal clear and frozen in time (complete with beer, mid-slosh) but with the background almost irrelevant:

Although not a huge party animal(!), I do like to document my extended family growing up, and trying to snap sub 5 year olds in the act of doing something unbearably cute in a dimly lit living room is absolutely a job for Xenon.

For the young, tech-savvy 20 somethings too, they're eating out most nights, partying several times a week, shooting casual shots in often badly lit clubs and apartments, and most of the photos will be of other people. Living, breathing, moving people. Which means that trying to freeze movement with an LED flash is, again, doomed to disappointment.

Yes, it's obvious from the above examples that Xenon-lit photos are rarely perfect - backgrounds are dark and you almost always get some degree of 'red eye' that has to be taken out later, on the phone or on the desktop - but they're, overall, better than LED-lit alternatives.

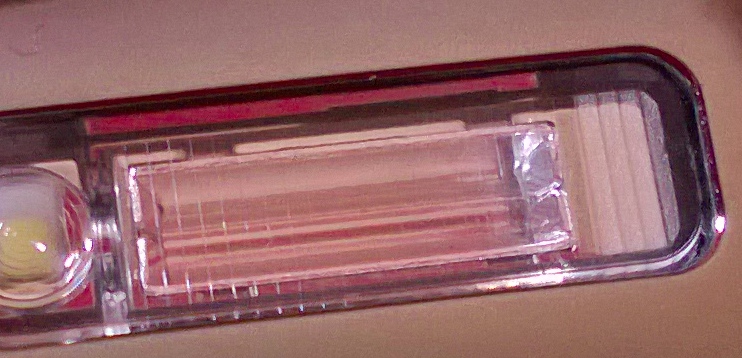

Which brings us to the physical requirements. The Nokia 808 PureView has two (count 'em) bulky cylindrical capacitors powering its Xenon bulb (shown at the top) - but then it has space to spare because of the physical size of the 1/1.2", 41 megapixel camera unit. However, even putting aside future flat capacitors, there have been other Xenon-equipped smartphones without too much of a 'bulge', not least the niche Android handset, the ill-fated Motorola Milestone.

The Lumia 920 is almost 11mm thick, but still fits in the hand well, and one would assume that a successor will be of similar form factor. 11mm is fine for fitting in a modest Xenon-compatible capacitor underneath the physical display, albeit not to the 808's specification. The latter also sported an LED for focus-assist, video lighting duties and 'torch' mode, and it's safe to assume that future Xenon-equipped smartphones will also have this flexibility.

Add in some intelligence in the camera software and maybe we really can have the best of all worlds, with the algorithms deciding when to fire the Xenon flash and how much extraneous context illumination to allow in, to fill out the scene?

Either way, I'm convinced that 2013 could be the year of Xenon. Whether the smartphones come from Nokia, Sony, Samsung or someone else. And in the meantime, if you fancy playing with Xenon again yourself, why not dig out your old 2007 Nokia N82 and have a blast down the pub?!