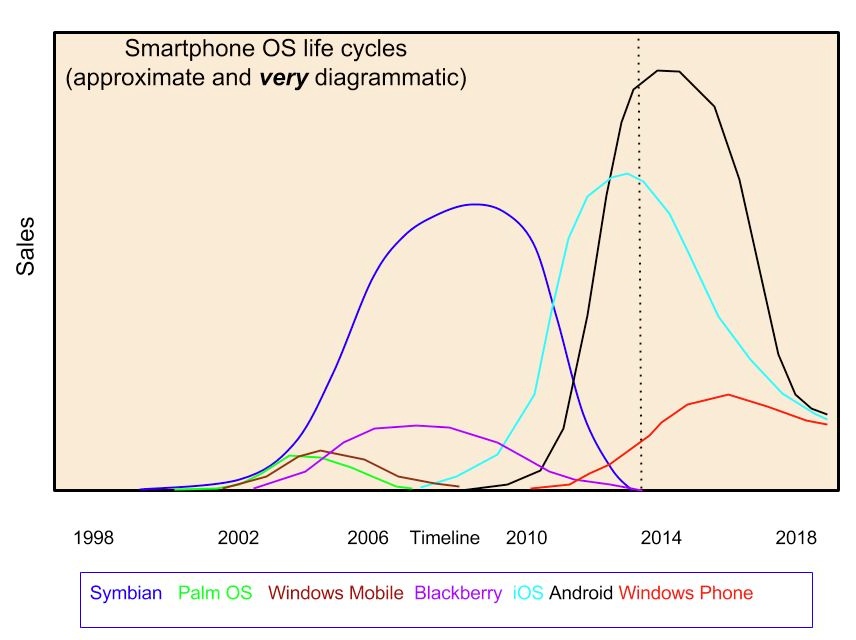

In the grand tradition of 'a picture is worth a thousand words', and please forgive me for minor inaccuracies in the axes (especially the 'y' axis), here's a rough overview of the sales in each of the seven smartphone software platforms of the last decade or so. Note that the dotted line is 'now' (i.e. September 2013, as I write this) and that everything beyond this is, of course, pure conjecture. But hopefully you'll spot the shape of each of the curves and get the point:

Now, legions of readers will be shouting that iOS, Android and (yes) Windows Phone won't be dying away by 2018, but remember that four years is an eternity in the mobile world - four years ago, Android was nowhere and the (plastic) iPhone's camera had only just acquired auto-focus. In four years time, maybe we'll be into another new phase of personal mobile computing - wearables, smarter, smaller, voice-aware PDAs (see the 'future' segment from this show, from 2011, for example) - who knows?

The big take away from the chart above is, of course, that all operating systems and ecosystems rise and fall. Of the clutch that heralded in the smartphone era, Symbian's S60 interface was massively dominant, with over 60% of the market at one point. Symbian's UIQ and Series 80 interfaces were dropped, Palm OS never really made the transition from PDA to smartphone as successfully as it perhaps should have done, while Microsoft's Windows Mobile was never able to fully shake the feeling that it was a stylus-centric PDA with phone features added in as an afterthought. Meanwhile, S60 sold by the many tens of millions per quarter by pretending to just be a 'phone', a trend that now sees the smartphone as ubiquitous in 2013 and outselling low end 'feature' phones.

The capacitive touch-driven iPhone's much celebrated arrival in 2007 was a bit of a slow burn in terms of worldwide sales and it took a couple of years for Apple to catch up with the rest of the smartphone world in terms of basic functions, but iOS was really motoring by 2010 and the iPhone 4. Android also took a couple of years to get going, but was finally able to combine iOS's capacitive touch with a fully cloud-aware operating system, and the rest is history.

Windows Phone, Microsoft's reinvention of the smartphone, tried to learn lessons from the iPhone and iOS (capacitive touch, superlative UI response, normob-friendly pseudo-multitasking, anything tricky - like a file system - hidden away from the user) and from Android (customisable start screen) while integrating the Internet even further into its core, with the aforementioned file system effectively manifesting in the cloud as SkyDrive.

But each of these operating systems is (or was) a product of its era. Symbian, for example, is much derided for its lacklustre web browser and the way connectivity isn't as seamless as on other platforms. But Symbian was created in 1998, when the standard way to get online was via packet-switched data on GSM and, even when GPRS came along, there were big financial issues in going online at all - hence all the 'go online?' prompts and checks. And remember that when Symbian Web first appeared it was revolutionary, being the first Webkit-based browser to run in a phone form factor - at a time when the iPhone was still a gleam in Steve Jobs' eye.

iOS (née iPhone OS) and Android were part of the brave new world of smartphones, of course, with connectivity baked in seamlessly, with flexible full-screen touch interfaces and serious computing and graphical power available for ambitious gaming and the ability to deal with mainstream web sites, which were getting more and more bloated, doubling and trebling in byte size. But will we look back on iOS and Android in four or five years time, explaining to our kids why iPhones and Galaxys used to be big sellers because they were well suited to mobile life in this early part of the decade, but that they were ultimately too restrictive for the next big wave of personal mobile computing?

Every smartphone OS has a peak, above - everything in life undergoes change. We're born, we grow up, mature and finally grow old and die, and the same is roughly true of software. After all, modern operating systems are almost as complex as a human body and subject to similar entropy and wear and tear (on their code).

In that light, it's no surprise to note the news from this week that Blackberry's long run is coming to an end - it, like Symbian, had survived well beyond Rafe's 'six years', but in each case it was with a certain number of reinventions and writhings towards the end. Blackberry had evolved into a smartphone platform after years as just a heavily message-centric device, but its reinvention (OS 10) came a couple of years too late.

As it is, there was a certain window of opportunity, between 2008-2010, for a company to take lessons for the 'brave new smartphone world' and produce mass market products for the 90% of people who don't want or (more usually) can't afford an Apple iPhone.

Windows Phone sneaked in at the very end of this window, in late 2010, and has been playing catch-up ever since, despite some innovative UI ideas and often some excellent hardware. The delayed start to Windows Phone's life cycle does perhaps mean that it's more future proof than iOS and Android and that its sales peak is still somewhere in the future, as shown in the chart. Maybe.

Blackberry, launching products based on its new OS 10 at the start of 2013, was a good two years behind the competition in this touchscreen slab form factor and, with its traditional QWERTY candybars becoming an ever more niche form factor, was always facing a nearly impossible task. That it failed isn't a reflection on the technical merits of OS 10, but more on the timing of its very existence.

I've deliberately talked in general terms above, in line with the diagrammatic nature of the chart, and I've also happily mashed together devices in with platforms and ecosystems, but hopefully the broad brush strokes ring true to you. Quoting from no less than the Old Testament: "For everything there is a season". Blackberry's is now over, so is that of Symbian, Palm OS and Windows Mobile, leaving just three current mainstream smartphone operating systems.

The really exciting thought is 'Where do we go next?' What will be in our pockets, on our wrists, mounted above our eyeline (etc) in 2018? Comments welcome!