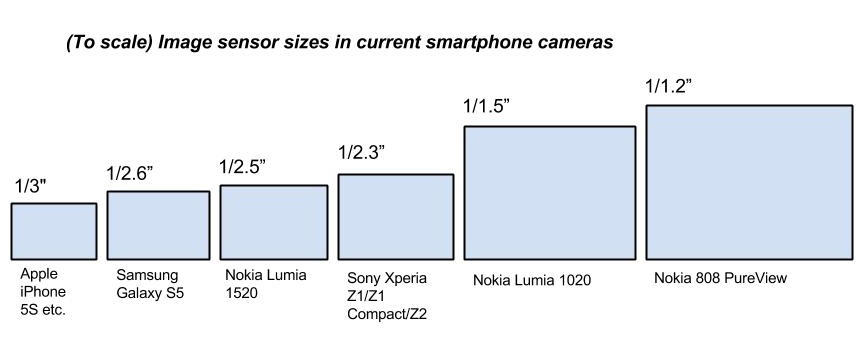

Am I being disingenuous in describing the Samsung and Sony phone camera sensors as 'tiny'? Perhaps a little. Samsung seemed really proud of the fact that it had stretched the sensor in its imminent 2014 Galaxy S5 to 1/2.6", but as you can see from the chart below, it's really not very far towards the ground-breaking (for phones) camera sensors in the Nokia Lumia 1020 and 808 PureView.

It's worth noting that the actual resolution of the sensor is fairly immaterial these days. Higher resolutions are usually used intelligently for oversampling (to some degree), reducing noise and improving pixel purity. What matters, ultimately, is the sensor size.

In case you're confused by the relationship between quoted sensor size and the areas depicted below, note that "optical format" (the number usually quoted) has a somewhat complex relationship to actual (plan) size of sensor, but as a rule of thumb the area 'goes as' the square of the optical format 'number', i.e. it's a square relationship and not a linear one.

Staggering as the chart above is (especially for fans of devices down at the lower end), it's also interesting to note that Nokia was using 1/2.5" sensors in its S60 (Symbian) smartphone range for ages, during 2007-2009, starting with the classic N95 range. So, where even the Lumia 1520 is hailed as having a large sensor today, in 2014, note that it's only matching what Nokia itself was doing in many tens of millions of classic smartphones six years ago.

Of course, other aspects of the technology have improved in the intervening years, not least image processor speed and sophistication, sensor sensitivity, the introduction of BSI (Back Side Illumination) and OIS (Optical Image Stabilisation) - but it's still worth bearing the N95-era benchmark in mind.

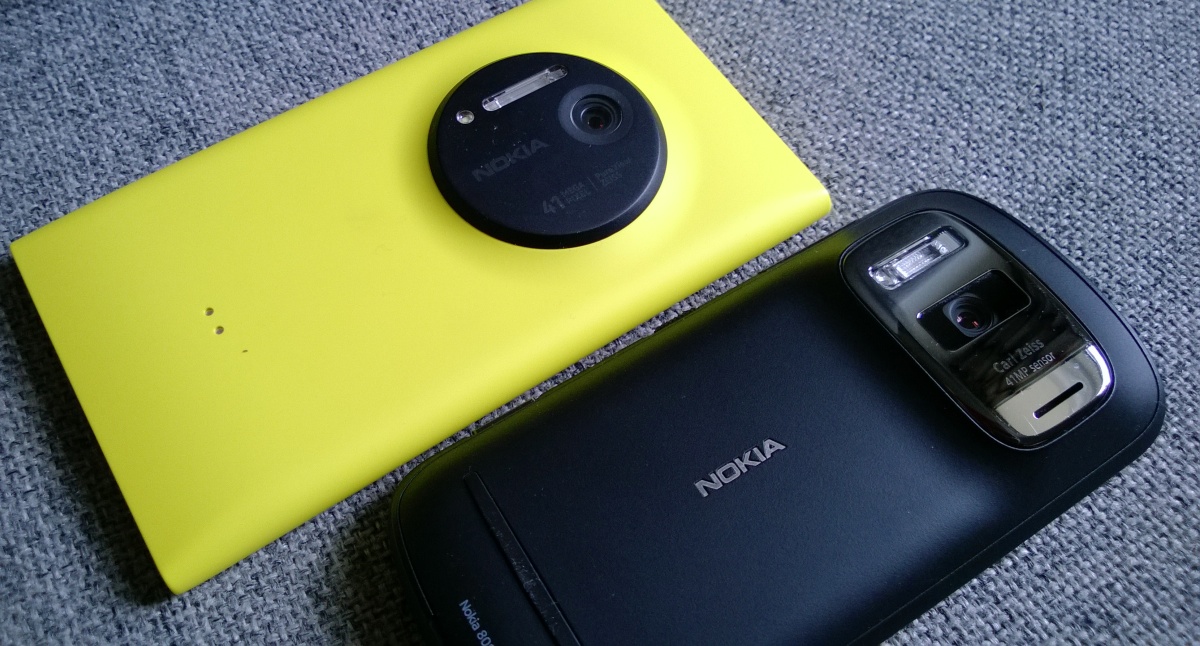

Given how relatively slim the Lumia 1020 is (only 14mm at the thickest part of the camera island), I find it odd that no manufacturer has tried to get close to Nokia's camera system yet - maybe the upcoming Oppo Find 7 will be the device that takes the 1020 head on?

Modern photography is, at heart, the science of getting pixels of light to register on an electronic sensor - and the more of them that do, the more accurate and consistent the result. So the larger the optics (the aperture of which is set relative to the sensor size) and the larger the sensor, the better.

So a significantly larger sensor, as in the case of (for example) the Lumia 1020 relative to that of the Galaxy S5, with an area ratio of around 3:1, means that much better results should be achieved. In fact, in the case of the 1020, there's also OIS to help out by allowing longer shutter times (i.e. more light) without shake or blur. Plus Carl Zeiss optics, for what they're worth, and a proper Xenon flash to keep the 'more light' theme going even when there's little ambient light.

But what do we see across the industry? A focus on faster and faster supporting electronics, with more and more sophisticated visual effects, and little priority given to simply including a bigger camera sensor. Now, admittedly, HTC's Zoe system, taking shots all the time so that it can capture a burst of photos starting before the shutter icon was tapped, is downright innovative, and the iPhone (and Nexus 5's) integrated hardware-accelerated HDR can produce very impressive results without needing a tripod. Plus a mountain of shooting modes that centre around taking a burst of photos and then post-processing them for special effect.

I'm not knocking all of this - innovation and intelligence in camera hardware and software is always a good thing. And such modes and tricks help close the gap to Nokia's pair of camera phone champions. But they don't get there in the end. I'm often quoted as saying "physics always wins". What I mean by this is that, everything else being equal, the device with superior physics will win, i.e. the larger sensor. Now, although it's hard to directly compare cameras hosted on different devices running under different smartphone operating systems, the size gap demonstrated above (e.g. a factor of 3:1 from the Lumia 1020 to the Galaxy S5), plus the OIS and Xenon, mean that there's a big mismatch in the physics. [Another snapshot example: the Nokia 808 PureView's camera sensor is SIX times larger than that in the Apple iPhone 5S.]

"Yes, but the Lumia 1020 takes a couple of seconds at least between photos!" is a popular retort. "When you're faced with kids and pets, this is too long and you'll miss the shot!" This is partly true and I've missed a few golden photos while waiting for my Lumia 1020 to 'process' the previous snap. But the photos, in such indoor, low light, fast moving conditions, that I get with the big sensor and Xenon flash on the 1020 are all sharp and usable, while the typical iPhone or Samsung Galaxy or Sony Xperia snaps will all be blurry messes to some degree.

Quoting from my own article "Stunning Black imaging":

No, not a pub shot mock-up from yours truly, but a real world shot of a different small relative. Two years old and never staying still ever - no concept of striking a pose, and the only way to photograph her reliably is with Xenon flash, as on the Lumia 1020. Again I've blurred her face to protect her privacy, but you'll get the idea:

It's this sort of shot which means that, once you've used a camera phone with Xenon flash (in my case, starting with the Nokia N82, back in 2007) you can't really go back. In this sort of indoor situation with kids, you could take a hundred photos with an iPhone or Samsung Galaxy and every one would be blurred. Or you could take just one with Xenon and get something you can share instantly around the whole family - crystal clear.

Yes, Nokia has experimented with fancy burst mode effects too, there's even a 'Smart Camera' mode in the main Nokia Camera application on the Lumia 1020. But you know what? Quality is lower, even under optimal circumstances, and I never use it. Every time I've tried, I end up with something with artefacts or noise or blur or some other weirdness.

In fact, in addition to my chart above, this photo (credit below) speaks volumes too...

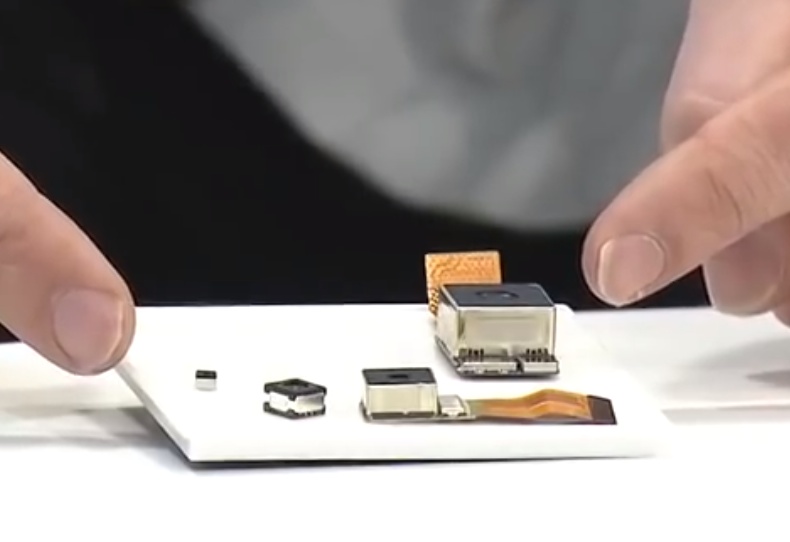

(From Nokia's Juha in his Engadget interview at CES 2014)

From left to right, a front-facing camera, an 'entry level' camera (probably 1/4", but not a million miles from the camera size used in most other smartphones of today), the Lumia 1520's 1/2.5" camera (so very similar to that in the imminent Galaxy S5) and finally, on the right, the Lumia 1020's 1/1.5" unit, positively dwarfing the rest. In fact, every time I look at this photo and then look at the Lumia 1020, I find myself somewhat incredulous that the cuboid above fits inside the sleek camera phone in front of me. The same goes for the Nokia 808, with an even larger camera body, yet fitted within relatively sleek lines.

But this isn't meant to be a 'rah rah Nokia' article, the key takeaway here is that, however many software and processing gimmicks a manufacturer adds to a smartphone camera, none of them has as much impact as a significantly larger sensor in the first place.

The 'All New HTC One' was leaked yesterday and I was asked if its rumoured dual 2MP/4MP cameras would combine to produce better photos than the 1020 and the 808. I was asked the same, in the past, about the 'clear pixel' camera in the Motorola Moto X and the 'EXMOR'-technology in the Xperia Z1. Whatever the innovations and advances in each new technology, they're small compared to the giant deficiencies in sensor size.

In each case my answer's the same: "Not a chance. Physics wins. Physics always wins."